Not for the first time, what started as a modest but interesting idea that popped into my head and that I thought could be fleshed out a little through a “quick blog” has ballooned into something much, much larger. So, this is the first of two “twin” posts discussing offshoots from and perspectives on my recent research into Kingston upon Thames, and how it commemorates its early medieval past. It serves as something of a scene-setter, but also a lot more than that; the second is a shorter and more polemical piece. Make yourself comfortable and begin!

I started thinking about the subject of this post when I was in Switzerland, on the first weekend of August, and an unexpectedly relaxing long weekend away (due in no small measure to it being far too hot to do anything active other than swimming). I took myself down something of a necessary wormhole of some of the more extreme medieval-tinged content available online, from the dubious outputs of a self-described historian and film-maker (apparently a sometime-Surrey resident) with a weird penchant for how great things supposedly were back in the early Anglo-Saxon period, to an interminable egotist-authored, school newspaper-quality “profile” of what’s been going on in medieval studies in recent years, one I’m glad to say has since sunk without trace (much like its author’s financial security).

A stupendously warm evening in Zurich, early August 2018

Four months later and I’m finishing writing with the British Library’s much-hyped Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition in full flow. Billed as a “once in a generation” show, I find its concurrence with the chaotic machinations of Brexit fascinating but also unsettling. It’s still not clear from all that I’ve read and heard about it what its narrative is regarding the formation of England, and of the English as a people. Are they told using the findings of current research, or (as per so much to do with the early medieval period) in a way that plays to its audience’s existing understanding of the subject matter, however basic and outmoded that may be? I’m going to say more about this issue in my next post, and I’m hoping to go to the exhibition in the next few weeks, so expect (or rather, don’t not expect – hell I wish I had more time to dedicate to this site) something about that in due course.

Although this post has evolved considerably in its breadth as I’ve written it intermittently over the past few months, at its heart has always been a desire to explore why, at times, people choose to believe demonstrable fiction over demonstrable fact. When it comes to manifestations of this in relation to the Middle Ages, all too often this arises out of a profound misconception of what we actually know (or can know) about whichever bit of the middles ages is under discussion, and a tendency to cleave to old ideas and cite only those people that propound and reinforce them. There’s so much wrong with medieval studies as currently configured that it’s easy to pick a target, highlight its shortcomings, and demand things should cease to be done in the current way with immediate effect. However, it’s one thing to demand that something outmoded is consigned to the dustbin, and quite another another to do so in concert with suggesting a replacement to institute in its place. The former is something you see more often and, while understandable and not without merit, does leave me feeling a little dissatisfied.

What I want to do here, while adhering to the latter approach, is nothing very earth-shattering. Simply, I wish to make the case for a new reading of the so-called Coronation Stone in Kingston upon Thames, one that is a good deal less lustred than the traditional interpretation I shall reject in the process, but that is more firmly rooted in an objective reassessment of the evidence so far as it exists or otherwise is recorded.

Introducing the Kingston Coronation Stone

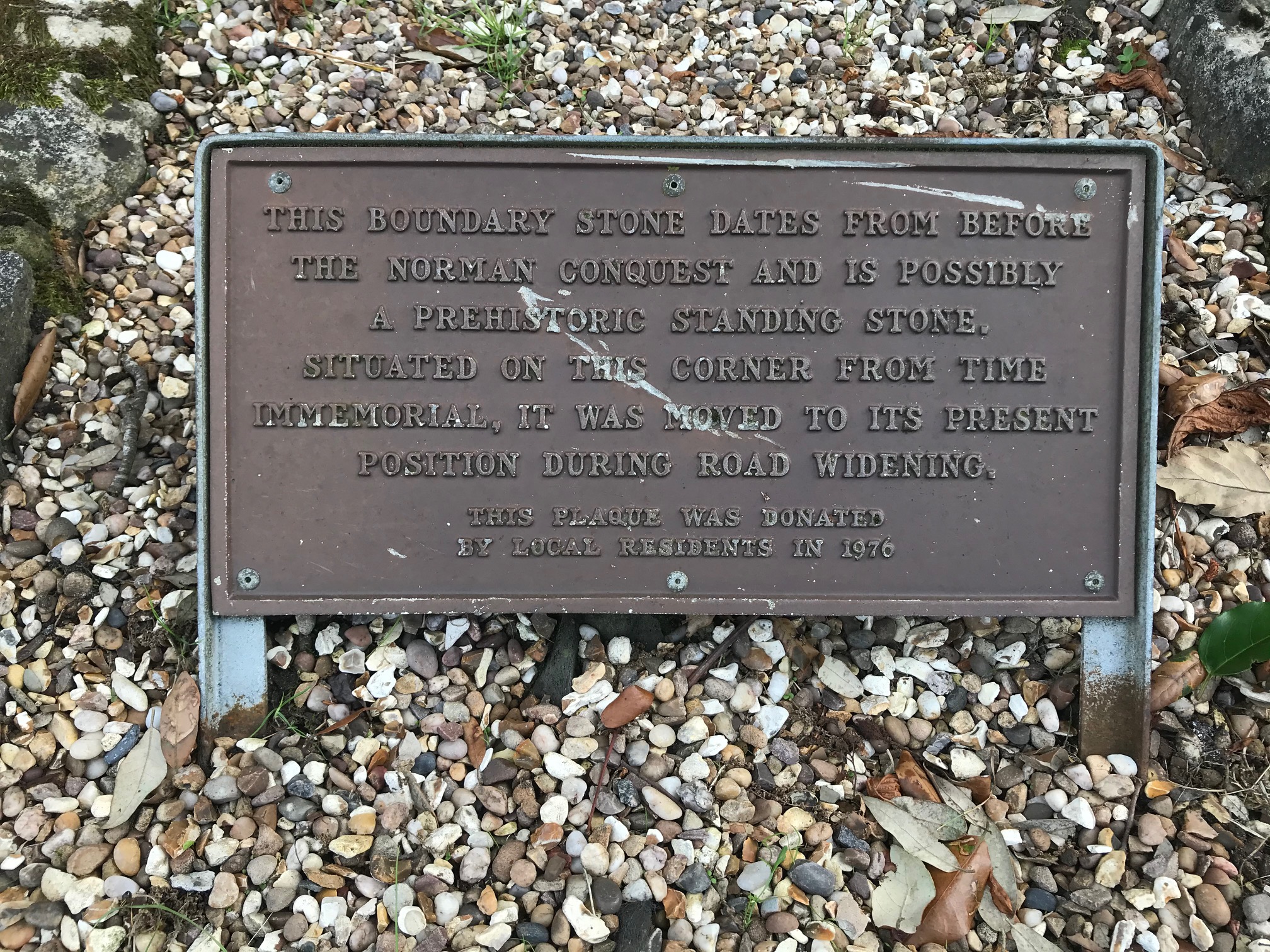

You can find the Coronation Stone sandwiched in a corner of the grounds of Kingston’s Town Hall (formerly Guildhall) between the High Street and the Hogsmill River. It’s set on a heptagonal granite plinth, behind chunky sky blue iron railings in between pillars topped with spears. The plinth bears the names of the seven kings it was/is claimed were crowned at Kingston in the 10th century CE, each spelled out in metallic “Old English” capital letters. This ensemble was created in 1850, and has continued a longer tradition of the stone peregrinating around Kingston town centre for more than a century earlier than that date. A modern metal plaque (late 20th century, at a guess) gives a description of the ensemble and a potted history of the stone, including the statement that ‘this stone was used during the ceremony of coronation by seven Saxon kings of England, who were crowned at Kingston upon Thames’.

North face of the Coronation Stone

East face of the Coronation Stone

South face of the Coronation Stone

West face of the Coronation Stone

Somewhat innocuous location aside, the structures under and around the stone make it look a good deal more impressive than it actually is — a grey-coloured, large-but-not-massive boulder. Were it to rest on or significantly closer to the ground than it does right now, it would have a decidedly underwhelming physical presence. In other words, its 19th-century setting – even if it is now relegated to the corner of the grounds of a municipal building – goes a long way to physically and metaphorically elevate it up to a level to which it arguably does not belong.

Separating facts from conjectures

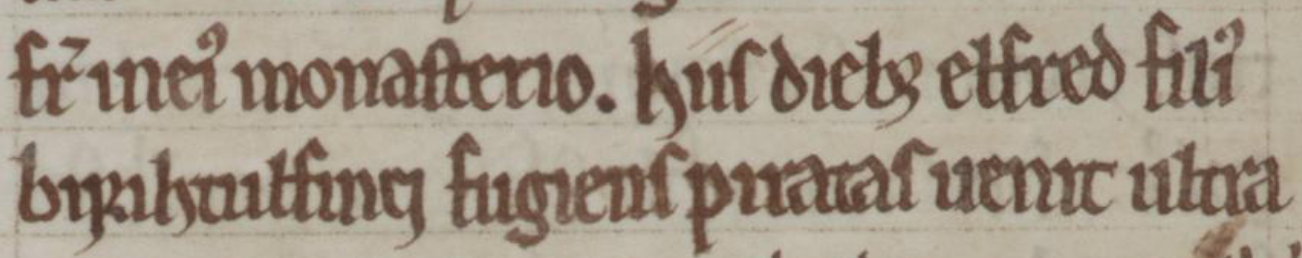

It might seem like this ostentatious steading means the Coronation Stone has been a feature of the settlement landscape of Kingston since time immemorial. Nothing could be further from the truth. Thanks to a number of post-medieval antiquarian accounts, and analyses of them by recent historians, we know a few salient facts about the stone, but also some speculations that have been elided with them (Butters 2013, 42-44, is now my go-to overview, and the source of what follows). Perhaps the key indisputable fact is that it is absent from all of the works in which it would be expected to be mentioned until publications of the mid-1790s (more on these in a bit), when direct references were made to:

‘a large stone, on which, according to tradition, they [i.e. new kings] were placed during the ceremony.’

These sources place the stone on the north side of All Saints’ Church, reputedly in the vicinity of the site of the demolished medieval chapel of St Mary. However, the foundations of the chapel were found on the south side of the church in 1926. It is possible something is amiss with our earliest relevant sources, and that north and south were confused in print back in the 1790s, but there is no independent evidence for the presence of the stone to the south of the church. It is tempting to follow Shaan Butters in her assessment of the situation; ‘it is a reasonable assumption that the stone had something to do with the chapel’ (2013, 43). But this reading rests on no more than an assumption, one that has not been tested as much as it ought to have been. This post, among other things, will offer a deeper, more critical evaluation of the scanty evidence that underlies it.

St Mary’s Chapel is known to us not only in written accounts, but also reasonably accurate engravings made in 1726. This is especially fortunate as, a mere four years later, the chapel was no more – demolished in the wake of its collapse as the result of one too many graves being dug inside or immediately adjacent to its walls. For a long time, the chapel was held to be a pre-Norman Conquest edifice, but has since been reassessed as having a greater likelihood of being slightly later in date, perhaps of the late 11th century (see Hawkins 1998, 277). Thing is, it’s dawned on me that what we see depicted in 1726 represented at least three phases of construction, with the lancet windows and majority of the masonry having an appearance consistent with a late 12th- or early 13th-century date; only the blocked and truncated west doorway can be positively suggested to have been earlier fabric.

The 1726 engravings: St Mary’s Chapel as it was at the time (the ‘Modern Porch’ was actually built in the Tudor period) and, more remarkably, a reconstruction of ‘the Ancient Form of the Building’. Taken from Hawkins 1998, 274 Figure 2.

Popular and unpopular opinions

I’ve long been aware of the Coronation Stone and its somewhat dubious pedigree, but had little cause to consider it at any great length until the past year or so, when Kingston became first an object of my research interest and then (separately) my place of work. I pass the Coronation Stone most weekdays now, rarely paying it much heed beyond a short glance in its direction, but ever so gradually the question “What was it?” has grown greater in my mind.

A view of the top of the Coronation Stone showing what may have been fancied to be its seat-like top. Note the coins = offerings to the Anglo-Saxon kings?

It’s not hard to see why the stone has been claimed to be some kind of repurposed throne. The way it’s presented nowadays (and has been since the 1850s, it would appear) means that its uppermost face is akin to a dished “seat”, just right for a royal posterior… Nevertheless, it doesn’t look much like a frith-stool, such as the Anglo-Saxon-period examples that survive at Hexham Abbey and Beverley Minster (nor, for what it’s worth, like the later example from Sprotborough in South Yorkshire). Likewise, you’d have a hard time squaring its modern form with any of the depictions of royal thrones found in manuscripts or embroidery of the tenth and eleventh centuries. But the coronations + stone = Coronation Stone formula has proven remarkably tenacious.

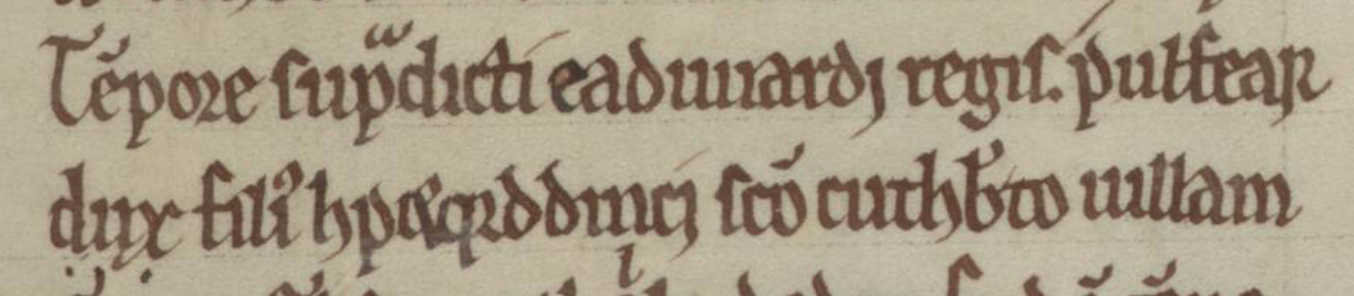

On the welcome page of Where England Began (set up to support ongoing fundraising efforts for All Saints’ Church, Kingston) is an embedded YouTube video featuring no less than Prof Sarah Foot stating categorically that Æthelstan was crowned upon the Coronation Stone (a little over 1 minute 40 seconds in). Which is a bit strange, since Foot has previously looked at Kingston and the Coronation Stone in her celebrated biography of Æthelstan. In that book, Foot offers, well, a historian’s take on matters; so, for example, the hypothesis of the stone being the last survivor of a stone circle gets a fairly positive citation despite the complete absence of any credible correlates in the region (Foot 2011, 245). Crucially, however, she doesn’t go so far as to claim in print that the Coronation Stone represents the ceremonial focus of the tenth-century coronation ceremonies at Kingston.

There’s a marked divergence between how the Coronation Stone is understood by, on the one hand, the public at large, and how it is viewed by historians and archaeologists on the other. It’s recognised by many who fall into the latter bracket that the Coronation Stone is unlikely to be, well, an Anglo-Saxon-period “coronation stone”. That this is not the line of interpretation found on the ASK website, for example, speaks volumes about how wild and sometimes ridiculous ideas have been allowed to go unchecked until the last 20 years or so. Since then, critical review of the historiography of the Coronation Stone has been done, and done very well, more than once.

The first detailed consideration of the evidence that I encountered was published by Duncan Hawkins in 1998. He provides a useful overview of the antiquarian accounts pertaining to the coronations at Kingston, and in doing highlights the comparatively late entry of what would become known as the Coronation Stone into the picture. His analysis is particularly useful for its reading of the passage in the 1793 edition of The Ambulator that comprises the first direct reference to the stone, which proves the tradition linking it to the coronations of the 10th century went back into the 18th century, but maybe not before 1730 and the collapse of St Mary’s Chapel at Kingston. He ends with the following conclusion:

‘Presumably the ‘kings stone’ was in fact nothing more than part of the fabric of St Mary’s Chapel.’ (Hawkins 1998, 275)

This interpretation has been taken up in an even more thorough analysis proffered by Shaan Butters in her extraordinary book ‘That famous place’: A history of Kingston upon Thames, published in 2013. As local history books go, it’s awesome – like a Framing the Middle Ages for a small corner of south-west London – so much so that I snapped up a copy for the purposes of writing this and future bits of research.

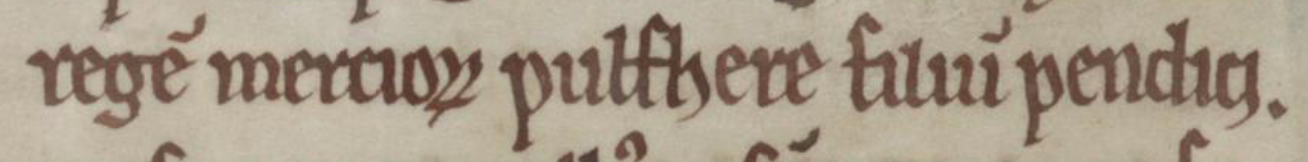

Butters does not simply rehash or paraphrase the previous objective analyses by the likes of Hawkins, but expands the scope to evaluate the possibilities for what the Coronation Stone originally was, and what it became (Butters 2013, 42-44). Especially useful is her dismissal of John Speed’s 1627 reference to ‘the chaire of Majestie, wherein Athelstan, Edwin and Ethelred sate at their coronation’ as having anything to do with the stone (Butters 2013, 44). This contradicts a lot of 19th- and earlier 20th-century writings, not to mention what is asserted on the metal plaque attached to the plinth beneath the stone, but is a clear-eyed reading of Speed’s words, and surely the correct one.

In view of this, I am happy to accept the conclusion Butters draws from it (and John Leland’s earlier Reformation-era reference), namely that there is not a shred of evidence for the Coronation Stone being of any significance whatsoever in Kingston in the 16th or 17th centuries. Contrast this with the bountiful records of the London Stone, stretching all the way back to the start of the 12th century (as charted by Clark 2010, 39-41). We must consider it highly likely, therefore, that the Coronation Stone was not a prominent feature of the urban topography of Kingston during the Middle Ages and in the centuries that followed.

A bizarrely dramatic view of the Coronation Stone (photographer and date unknown), featured in a permanent display at Kingston Museum

Butters, like Hawkins, sees the reported spatial association between the stone and St Mary’s Chapel as a meaningful one. Amongst the more credible explanations she entertains is that the stone ‘could have been imported as Saxo-Norman building stone’ –although she immediately caveats this by opining that ‘such an ancient, massive stone’ surely had less prosaic, and perhaps instead numinous, qualities (Butters 2013, 44). This is very probably influenced by an early (and in places horribly racist) article by William Bell, based on a paper he gave in 1854, that was published in the very first volume of the Surrey Archaeological Collections, placing it in time shortly after the “elevation” of the Coronation Stone to its present ornate steading.

In amongst all the Victorian verbosity (oh boy does Bell go on and on…) and spurious numerological conjecture, the idea is proffered that the stone is, or rather came from, a ‘Morasteen’ equivalent to a now-lost stone circle with later recorded Swedish royal associations near Uppsala in Sweden (Bell 1858, 33-35). In short, Bell posited that ‘our Kingstone stone would be only one of a smaller circle of thirteen, surrounded by a larger outer girth of somewhat indefinite but frequent multiple of four’, and moreover – on the basis of an incorrect place-name etymology – that it came to Kingston from Runnymede (Bell, 1858, 40, 45). It’s such a horrendous article that I’ll leave it for anyone who is interested to read through it for themselves. For the rest, the important thing to keep in mind is the possibility that the stone was of prehistoric significance (cf. Johnson and Wright 1903, 63 and 116, for the interpretation that it was ‘a broken menhir’).

To be more specific

Shaan Butters gives what is in effect a state-of-the-art summation of present scholarly understanding of the Coronation Stone when observing the following:

‘It does, on balance, seem likely that the coronation stone had been used as building material in St Mary’s Chapel […] But this still leaves us with questions about the stone’s significance, and how it came to be in Kingston in the first place’ (Butters 2013, 44)

What I want to do here is take the discussion one step further, to develop Butters’ last postulation by proposing a specific origin for the Coronation Stone. To cut to the chase, my hypothesis is that the stone formed part of the foundations of St Mary’s Chapel, which would place it within a surprisingly large group of medieval churches and chapels marked out by this characteristic.

I first encountered such a stone at Stonor Park chapel in the Chilterns. The Stonor Park website claims ‘the original Chapel of the Holy Trinity was built in the late 13th Century on the site of a prehistoric Stone Circle’, a conclusion founded on how the south-east corner of the chapel ‘rests upon one of these mystical stones – a symbol of Christianity adopting the ancient site as its own’. If I’m not mistaken, the “mystical stone” in question is a sarsen boulder, one that projects externally in a very conspicuous fashion. Interestingly, the website also pedals a line about how Stonor is one of just three British (medieval) chapels that ‘have always been’ of Catholic denomination; in other words, another suspiciously “remarkable” story for which the supporting evidence is lacking.

The idea of making the link between a sarsen “foundation stone” (for want of a better term) and the Coronation Stone popped into my head upon contemplating the very similar dating of Old St Andrew’s, Kingsbury, not so many miles distant from Kingston in north-west London. When I visited a year or so ago, I noticed a big stone, perhaps a mite smaller in size than the Coronation Stone, lying beneath the south-west corner of the building. Somehow it escaped my notice that there is an even bigger slab-like stone beneath the church’s north-west corner! To those more observant than I, the two stones (which may or may not be sarsens) are basically every bit as visible externally as their cognate at Stonor. A word of caution though; what look to be recently-created or renovated brick gutters surround the feet of the walls externally, and have respected the stones in such a way that it is conceivable they may have served to uncover more of the stones than was ever visible previously.

Boulder (looking more like ironstone than sarsen?) at the south-west corner of Old St Andrew’s, Kingsbury

My scouting around for other published London-area analogues has failed to find much thus far. Downriver from Kingston at Barnes, archaeological investigations in the wake of a major fire at St Mary’s church in 1978 identified multiple phases of growth from an original earlier 12th-century single-celled masonry structure. Among the remains of this first phase were two ‘large stones’, tentatively posited to have formed part of the church’s east wall (Cowie and McCracken 2011, 12; cf. 6 Fig. 5). These stones are of unspecified type, and of a smaller size than the Coronation Stone, so their relevance to this study is uncertain. Dan Secker, in a brand new article (albeit one that’s been on the internet in an earlier incarnation for a while now), draws attention to a squared-cornered ironstone ‘block’ in the foundation of the north-east corner of the late 12th-century tower of St Mary’s, Harrow. At less than 60cm in its east-west dimension, again it appears to be a little on the small side in comparison to the Coronation Stone (Secker 2017, 84-85 including Fig. 12). So, church archaeology from the London area, at least work of which I am aware, doesn’t add much.

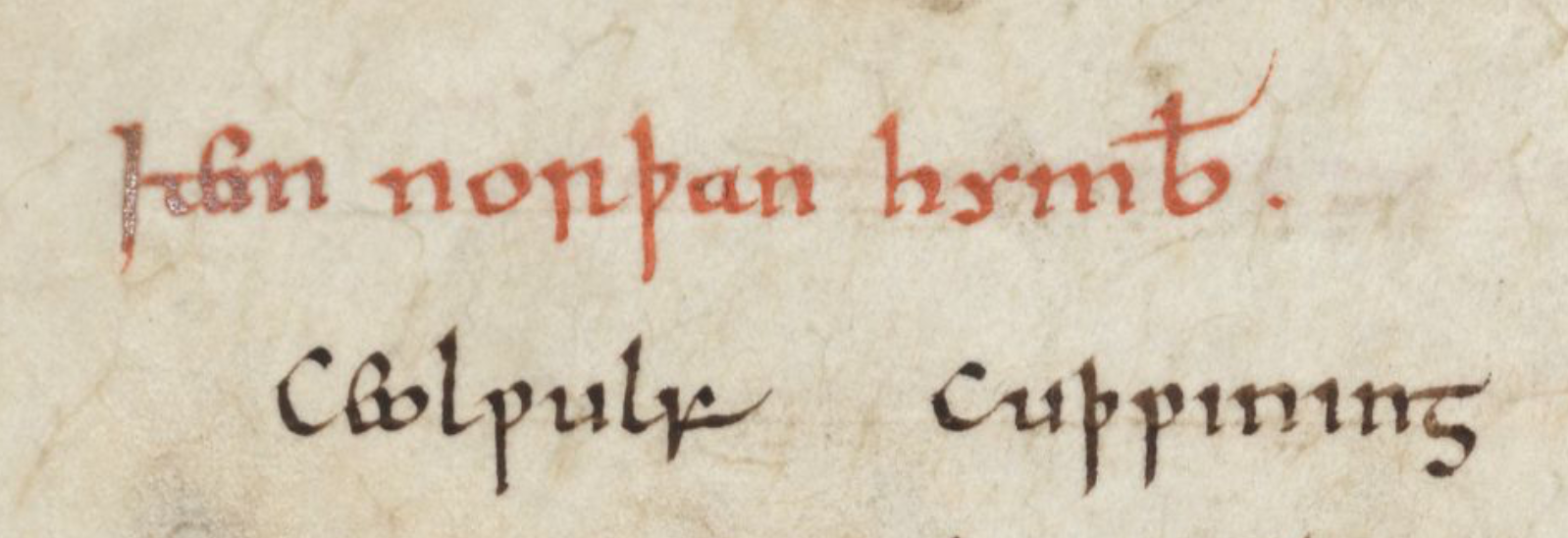

In starting to look for possible explanations, it is true that Kingston and Kingsbury share the same first name-element, namely Cyninges, the genitive singular inflections of OE cyning ‘king’ (Mills 2010, 138, 139; note Cyngesbyrig 1003×1004 in S 1488, often cited as the earliest attestation of Kingsbury, is all but certain to pertain to land in St Albans and environs). Maybe there is a recurrent pattern to be observed here, a connection between sarsen stones, places associated with “Anglo-Saxon” royalty and church buildings, but I don’t buy it. I only know of and hence have instanced Kingsbury because I happened to walk past it last year. There could be (indeed, probably are) other instances in the Greater London area. Moreover, even if they are the only two, this is hardly a statistically-significant sample upon which to argue for a correlation.

Google sarsen stones and medieval churches, on the other hand, and you’ll find lots of examples from across southern and eastern England. There are seemingly very thorough local lists of sarsens (and more) in greater East Anglia and the city of Winchester, providing useful parallels to the Stonor Park chapel in the form of the stones poking out of the corners of churches such as St John’s Winchester (east end), Boxted in Essex (south-west corner), and Pakefield in Suffolk (?west tower). Then there are the blogs and websites that highlight other examples, like the sarsen boulders which can be viewed beneath the present floor surfaces of the churches at Alton Priors, Wiltshire, and Eversley in Hampshire. It is important to note that these last two examples are both situated within the footprints of the current church buildings, rather in their external wall foundations.

Peek-a-boo: the sarsen boulder beneath floor level adjacent to the font towards the west end of St Mary’s, Eversley. Photo copyright of the British Earth and Aerial Mysteries Society/Ken Parsons, reproduced in good faith until such time as I make it to Eversley and take a snap of my own

I am also immensely grateful to Katy Whitaker for discussing the use of large sarsen stones in churches and sharing a snippet of her PhD dataset that hammers home just how many churches in Wiltshire and Hampshire contain or are otherwise closely associated with sarsens (including some very close to the Surrey border, like aforementioned Eversley and also Farnborough – where there’s even a suitably-named pub nearby). This is a subject that deserves MUCH more concerted study, and Katy’s current PhD research on the historical exploitation of sarsen should go some of the way towards achieving that (check out her artefactual blog for more sarsen stories). In the meantime, it is already abundantly clear that big sarsens (and boulders formed of other types of rock) are a not-uncommon feature of the foundations of medieval church and chapel buildings.

One thing that unites a lot of the sarsens in the areas mentioned above is their coincidence with tracts of chalk geology. This does not apply to Kingston, set on a gravel island in the middle of the Lower Thames Valley. Which invites the question; are sarsen stones capable of being found in a location like the Kingston ‘central island’ naturally, or did they have to be imported? As far as I can ascertain, the answer is – yes, probably. Sarsen is, according to, um, its Wikipedia entry, a kind of silicified sandstone formed in the last 23 million years by a multi-stage process involving the leaching of Lambeth Group sediments (a mix of gravels, sands, silts and clays that overlie the various formations of the Chalk group), followed by the cementing of the sandy elements, to form a dense, hard rock (a Cenozoic silcrete, to be precise) that formerly covered much of the area of southern England.

“The Kings Stone”, a hefty sarsen slab located beside The Maultway close to its junction with Red Road, Camberley, as seen on Google Streetview in September 2008

Sarsens are common on the sands of the Bagshot Beds, characteristic of north-west Surrey and adjacent areas. I’m not sure I’m permitted to divulge too many details of particular things I do as part of my job, but I think it’s okay to recount in general terms that not so long ago we received a report of the (re)discovery of the above sarsen boulder, said to be known locally as The Kings Stone, by a roadside near Camberley. According to the reporter, sarsens are frequently encountered in the course of roadworks in this part of Surrey, and a local blog has drawn attention to the nearby stones atop Curley Hill (alias High Curley) and on Brentmoor Heath. The lost Basing Stone, on record at least as far back as the mid-15th century (PNS, 153), may have been another example from the same area.

Several miles to the east, Wisley parish has been said to be the provenance of many sarsen ‘blocks’, including one used as the threshold of the porch protecting the main doorway into its 12th-century church (Ashington Bullen n.d., 4). Having no geological training, I don’t know if the formation process described above in concert with subsequent weathering and fluvial action could result in sarsen boulders at locations like Kingston further north and east in the Thames valley. Even if this is not the case, it has been demonstrated that there were sources of sarsen only a matter of miles away from Kingston. Moreover, it has also been shown that there is ample evidence both past and present for sarsen stones existing in locations without any need for their removal to a church, or the construction of one over them.

Taking a closer look at the archaeology of St Mary’s Chapel

Analogy is all well and good, but it can only get you so far. And in this case, that’s not very far at all. To really gauge the validity of my hypothesis, what is needed above all else is a much closer look at the archaeology of St Mary’s Chapel and how the results may or may not accommodate it being the provenance of the Kingston Coronation Stone. Understanding the archaeology of the chapel is not as straightforward as one might hope. Its site was relocated and “excavated” in October 1926 in a rather shonky bit of archaeology directed by W E St Lawrence Finny, a barrister by profession and in his day something of an all-round “Mr Kingston”. Be this as it may, his excavation report published the following year does provide a few pieces of credible information about the physical remains of the chapel building.

Commemorative window in Kingston Museum, presented by W E St John Finny, in his capacity as Mayor AND Deputy High Steward of Kingston

Finny refers to uncovering wall foundations formed of ‘large flints somewhat loosely bonded together with lime mortar, not well mixed’ (1927, 217). This is born out by the 1726 illustrations of the chapel, which show rough, dark walling at the lowest levels. The much finer masonry above was identified by Finny as Reigate Stone; a plausible possibility, although it is not clear if this was based on excavated fragments or a deduction from the 1726 drawings (Finny 1927, 218). Nowhere does he mention sarsen being used as a building stone, although the relative brevity and vagueness of his reporting of the details of his excavations (even for the standards of his day – compare Lowther 1927) could account for this.

Finny provided some particularly interesting information about the corners of the chapel. Having reported that ‘the foundations of the four corners had fortunately escaped destruction’ (something not clear from the single plan accompanying the article text), he went on to state the following;

‘All the corner cut stones shown in Manning and Bray’s picture have disappeared, sold to a contractor at the destruction of the Chapel’ (Finny 1927, 218).

The results of the 1926 explorations, which seem to have entailed little more than “wall-chasing”, were not published to a sufficient level of detail to be certain that the Coronation Stone was not once located at one of the four corners of the chapel, and was separated from the cut quoin-stones at the time of its demolition. Furthermore, it is clear from the way the imposts of the blocked west doorway of the chapel are depicted in the old engraving that the ground level outside the chapel was considerably higher than when it was first built. Taking these points on board, it is still perhaps marginally better to err on the side of optimism and deduce that it was not in an analogous position to the stones at Kingsbury etc. Perhaps it was once secreted beneath the floor within the footprint of the chapel, as at Alton Priors and Eversley (much less likely in view of its dimensions is that it served as a doorway threshold such as at Wisley).

The ground plan of St Mary’s Chapel, Kingston, as reconstructed from the 1926 excavations, and published in Finny 1927, 216. Note that no indication is given of the sections of wall foundations uncovered in 1926, nor of the other locations investigated but that produced negative results.

Partly in the hope that it might appraise one or more liturgical text that helps to explain why large boulders were buried beneath the floors of churches, this autumn I read Helen Gittos’ superb Liturgy, Architecture, and Sacred Places in Anglo-Saxon England. It doesn’t, because no such text survives, but Gittos does cite certain things that are perhaps of some relevance here. In her discussion of rites for dedicating churches, she draws attention to the blessing of ‘the platform on which the church stood’, and extrapolates that this represented a sequential, symbolic “construction” from the foundations upwards. Certainly, the officiating bishop stood in the middle of the church to perform the blessing (Gittos 2013, 232). Could the stone have marked the middle of the chapel, and been associated with its dedication ceremony?

In material terms, Gittos (2013, 235-36) notes tiled pavements were important and sometimes hallowed features of late Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman-period churches. Finny uncovered a number of plain and originally glazed floor tiles that were subsequently identified as ‘identical with those found at Waltham Abbey, built by Harold, and very similar to the pre-Conquest floor tiles in St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate’ (1927, 217-18). Neither of these churches is among those mentioned by Gittos as being the provenance of late Anglo-Saxon-period polychrome relief tiles (2013, 235, also 237 Fig. 81), so it’s uncertain whether Finny’s tiles were of the same type. Even so, it could well be the case that the floor of St Mary’s Chapel was an important and meaningful feature of its first phase – and the same might the same be said of anything placed in the ground before the tiles were laid. Finny (1927, 217) was explicit that the earliest tiles he found ‘were laid upon a bed of lime mortar which rested on the virgin soil’, so if this was true of the entirety of the chapel’s internal floor area then it suggests the Coronation Stone served no structural purpose.

In the end, the limited extent of Finny’s investigations in turn limits what can be said with any degree of certainty about the hypothesis that the Coronation Stone once formed part of the foundations of St Mary’s Chapel.

A Prehistoric pre-history?

As has been touched upon already, the narrative of Christian succession of a “pagan” site is an exceptionally common one. All too often this is in spite of a lack of suitable evidence, but also in the context of no relevant archaeological work (in the broadest understanding of the term) having been undertaken that might discover such testimony. Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence and all that… In Kingston’s case, as with so many of the sarsen-linked churches, a much greater time-depth going back millennia is often invoked, linking the stone with an otherwise completely destroyed prehistoric megalithic monument.

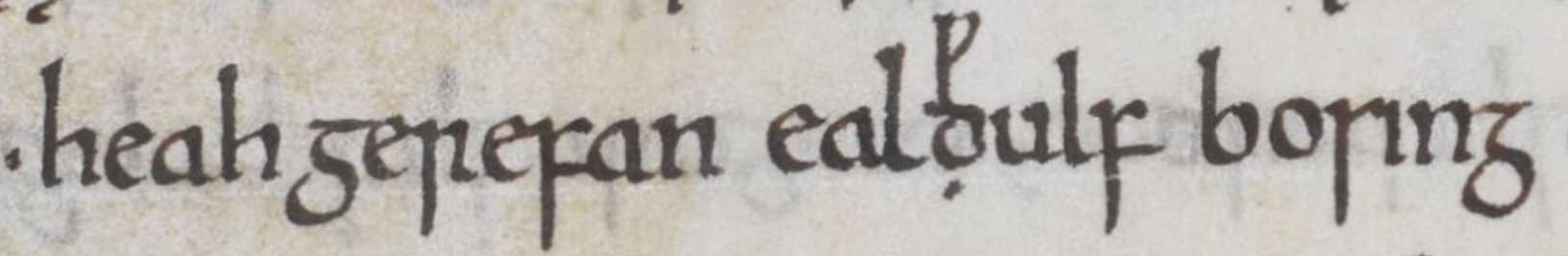

I don’t want to get into a chicken-or-egg discussion as to whether the Coronation Stone was brought to the site of St Mary’s Chapel, or whether the latter was built on top of it. The truth of this cannot be known. That it was a pre-existing feature of the so-called ‘central Kingston island’ is another matter; as Butters (2013, 56) posits, there exists the possibility that ‘the great sandstone boulder now known as the coronation stone was already on the island’ at the time of the chapel’s establishment, and thereby contributed to the numinous qualities of the location. Kingston was also the name of a Hundred, and it is likely that its meeting-place was in what later became the medieval town. It is noteworthy (though perhaps nothing more) that the Hundred immediately to the east was Brixton, OE Beorhtsiges-stān “Beorhtsige’s stone” > ((æt) brixges stane, (to) brixes stan in 1062: S 1036; Mills 2010, 33), implying a focal stone of unknown origin at its assembly site beside an old Roman road at Brixton Hill.

One way of looking at the situation is by comparing suburban Kingston and its surroundings with the much less built-up areas further south and west in Surrey. It has long been recognised that there are no indisputable prehistoric standing stones/megalithic monuments extant or on reliable record in Surrey, but several possibilities (in addition to the Kingston Coronation Stone) have been proposed all the same (as collated by Field and Cotton 1987, 81). Another instance, and a particularly intriguing one at that, is (to) þe stondinde stone ‘the standing stone’ mentioned in the bounds of Chobham probably composed in the mid/late 11th century and added to the much earlier text of S 1165; it may be recalled in the minor place-names Mainstone Hill and Bottom (Kelly 2015, 112, 114). Ultimately, however, none of these is especially convincing, including the instances north of the Downs once the sarsens of the Wisley and Camberley areas are invoked.

Shifting big rocks around would have been a hard job, but evidently it was one that was undertaken, and the reported presence of Reigate Stone as the main building material in the walls of St Mary’s Chapel (Finny 1927, 218) further underscores how stone was imported from considerable distances away when required – in this case from the southern foot of the North Downs ridge. And no matter many ecclesiastical buildings are held up as potential analogies to St Mary’s Chapel, it will always remain a possibility that the Coronation Stone had been introduced to the central Kingston island previously in connection with its function as a major early medieval assembly-place.

A number of plaques and patches of reconstructed rubble foundations marking the extremities of St Mary’s Chapel as relocated by Finny and friends can be seen in the southern part of the churchyard of All Saints’, Kingston

To sum up, there are some “archaeological” signs that the Coronation Stone did not undergird one of the corners of St Mary’s Chapel prior to its partial collapse and consequent complete demolition, which may go some way towards bearing out the idea that it came from beneath the floor of the chapel (or may not, depending on personal opinion!). The fact that we have testimony for details of the interior of the chapel, but none whatsoever for the presence of the stone, would fit with it being an under-floor feature. If it was located centrally, this would naturally add to the interest of the stone and invite speculation as to the reason for its presence in that particular position; given what Finny says about what would appear to have been the original tiled floor resting on nothing more than a bed of lime mortar, it is hard to deduce a structural purpose for it being there, unless as the pad for a heavier feature above, such as an altar? That said, the deeply undistinguished history of the stone in the decades after its removal from the chapel site does suggest we should not feel too compelled to see a thread of continuity in the memory of exactly where the stone was discovered.

Conclusions

The more I looked at the subject of, well, let’s be honest, big old stones, the more I came to realise that the story attached to the Kingston Coronation Stone is not quite as remarkable as it might seem at first. Consider the so-called Soulbury Boot in Buckinghamshire. Depending on which source you trust, it’s lain on the same spot for either 11,000 or 450,000 years – quite a discrepancy, and it’s far from clear that either figure is based upon solid fact. This immense age nevertheless inspired incredible strength of opposition to the idea that it should be moved from its present, middle-of-the-road location to ease the passage of motor traffic (it ended up being “protected” by some painted white lines).

The London Stone in its new home, December 2018

I mentioned the famous London Stone much earlier in this post. Considerable fanfare attended its temporary relocation to the Museum of London, and its very recent return to its previous (but not original) location has been equally prominent in various media. So, despite its much reduced size, arguably the London Stone has not been so much to the fore in the popular imagination since Jack Cade’s day (heck, it’s even on Twitter!) For all its credible documentary history, which stands in marked contrast to the Coronation Stone (and Soulbury Boot), it has also generated a body of fallacious legends and conjectures that are not easily distinguished from fact. Here again, we also find the lessons learnt from good scholarly work debunking some of the urban myths attached to the London Stone (as detailed in John Clark’s excellent 2010 article) not being applied more generally. It comes as little surprise, therefore, to find that recently an innocuous stone on a street corner in the City of London was put forward as a remnant of the demolished Ludgate.

Just as there’s a reflex in family history to find a compelling origin story, so there seems to be a desire for unexplained lumps of rock to be both explicable and “ancient”. To satisfy such desires requires the acceptance and amplification of the ahistorical, and hence the fabrication and perpetuation of myth. The end result is something that seems unimpeachably authentic because it defies easy and obvious explanation. From the examples I have collected and assessed above, this seems to be equally true for urban contexts as rural ones.

Let’s finish by returning to Kingston. It’s perhaps important not to get too excited by the prospect of what the Coronation Stone might represent. Sarsens and other sorts of very large stones occur in the foundations of too many medieval churches – and more to the point, churches without the same associations with elite assembly and power that Kingston has – for there to be a credible universal explanation of their presence, let alone any specific associations with “royal” places. Indeed, it is also important not to lose sight of the fact that there are far more large sarsen stones that exist entirely independently of any present or past connection with the fabric of a church building. (It is tempting to wager that the majority of medieval churches contain(ed) no large boulders in their foundations; however, without comprehensive fieldwork and intrusive archaeological evaluation this is pure speculation that may very well be untrue.)

It must be reaffirmed that there is no unequivocal historical or archaeological evidence for the Kingston Coronation Stone ever having formed part of the fabric of St Mary’s Chapel, be it as part of the foundations or an internal feature. Nonetheless, if the regional body of evidence for big stones, especially sarsens, in the lower levels of ecclesiastical buildings is accepted as being relevant here to the point of providing an explanation of from whence the stone came (i.e. the chapel’s foundations) then some tentative suggestions can be offered. If the reported results of the one poor-quality piece of archaeological evaluation of St Mary’s Chapel are to be trusted (and the more I think about this the less positively I view them), the stone does not seem to have been sited at one of the corners of the chapel. This being the case, it might be inferred that the stone once lay beneath the floor. If this postulation is correct, whatever the reason(s) for the stone being in such a location, they are unlikely to be structural. However, this does not compel the acceptance of a “Christianity triumphing over stone-worshipping paganism” narrative by way of an explanation.

We will never know precisely when and why the Coronation Stone first arrived on the central Kingston island, and what (if any) significance it held in the early middle ages. Nevertheless, it can be concluded to represent two things: just possibly a stone of prehistoric and undocumented early medieval significance, and, more certainly, an object to which completely speculative associations regarding Kingston’s early medieval status and limited recorded history have been and may continue to be attached.

REFERENCES (hyperlinked where available online)

Ashington Bullen, R (ed.), Some materials towards a history of Wisley and Pyrford parishes (Guildford: Frank Lasham, no date [post-1906?])

Bell, William, ‘The Kingston Morasteen’, Surrey Archaeological Collections [SyAC], 1 (1858), 27-56

Butters, S, ‘That famous place’: A history of Kingston upon Thames (Kingston upon Thames: Kingston University Press, 2013)

Clark, J, ‘London Stone: Stone of Brutus or Fetish Stone—Making the Myth’, Folklore, 121:1 (2010), 38-60

Cowie, R, and McCracken, S, ‘St Mary’s church, Barnes: archaeological investigations, 1978–83’, SyAC, 96 (2011), 1-47

Field, D, and Cotton, J, ‘Neolithic Surrey: a survey of the evidence’, in J Bird and D G Bird (eds.), The Archaeology of Surrey to 1540 (Guildford: Surrey Archaeological Society, 1987), 71-96

Finny, W E St Lawrence, ‘The Saxon church at Kingston’, SyAC, 37 (1927), 211-19

Foot, Sarah, Æthelstan: the first king of England (Yale University Press, 2011)

Gittos, Helen, Liturgy, Architecture, and Sacred Places in Anglo-Saxon England, (Oxford: University Press, 2013)

Hawkins, Duncan, ‘Anglo-Saxon Kingston: a shifting pattern of settlement’, London Archaeologist, 8:10 (1998), 271-78

Johnson, W, and Wright, W, Neolithic man in North-East Surrey (London: Elliot Stock, 1903)

Kelly, S. E., ed., Charters of Chertsey Abbey, Anglo-Saxon Charters, 19 (Oxford and London: Oxford University Press for The British Academy, 2015)

Lowther, A W G, ‘Excavations at Ashtead, Surrey’, SyAC, 37 (1927), 144-63

Mills, A D, A Dictionary of London Place Names, 2nd edition (Oxford: University Press, 2010)

Secker, Daniel, ‘St Mary, Harrow-on-the-Hill: Lanfranc’s church and its Saxon predecessor’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 68 (2017), 73-89